|

|

|

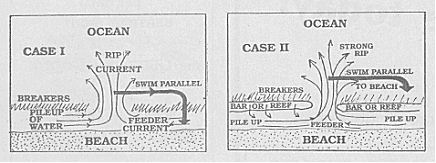

Rip currents, Runouts and “undertow” Every year, in almost every body of water large enough to generate waves 4 to 6 feet high, a number of incidents of swimmers caught in “undertows” occur. We oceanographers call them “rip currents” and many lifeguards call them “run-outs”, but by any name they can be terrifying to the uninitiated or weak swimmer. They consist of a rapidly flowing current running from the beach area, inside the breakers, out to sea. In most cases they flow faster than a person can swim, even with swim fins on, and they carry one out well beyond the surf. But this is only part of the problem! Imagine that you are playing in 4 or 5 foot breakers, diving through them and body surfing back to the beach, generally unconcerned because you are only a few feet from the warm sand. Suddenly your feet don’t touch bottom anymore and you notice you are farther from the beach. “No sweat.” You turn and swim for the beach, only a few feet away, where the sunbathers are so close you can watch them applying suntan lotion to each other. It is a quiet, almost pastoral scene. But they are getting further away! You put on a burst of speed but they still get further away. Now PANIC, the great killer, appears. You are scared and put everything you’ve got into one last spurt for the beach. You are typically, out of shape and soon, gasping, take in a mouthful of salt water and sink. The rip current has claimed another victim. Because you reduced you buoyancy by inhaling a lot of seawater, replacing air in you lungs, sometimes your body sinks. It was not the undertow pulling you under, it was the inhaled water making your body negatively buoyant that took you under. Either way it may well have been fatal! The terrible thing is, it was so unnecessary. A very simple rule will save your life if you are ever in this position. SWIM PARALLEL TO THE BEACH. Refer to the drawing to see how and why this helps. The rip is a narrow stream and, once out of it, you can turn toward the beach in perfect safety. It has saved many lives and could save yours. Remember this rule. And now the reasons for rips. There are two main cases for rips on open coasts. One is for a coast or beach with no underwater obstructions. The scheme works like this. As waves cross the ocean in deep water (defined as being deeper than half of the distance between two wave crests, normal to the crests) the water under the wave moves in circular orbits, with very little forward motion of the water. It is hard to believe that only the wave form advances. When this wave gets into water shallower than half the distance between the crests, it begins to drag the bottom and changes occur in the wave characteristics. It shortens as the forward crest slows down and the following crest catches up. As it shortens it gets higher, exactly what the surfer looks for on a beach. As it gets shorter and higher it gets steeper until the height becomes greater than 1/7th of the wavelength at which point the crest falls forward and the wave breaks. We know this as a plunging (Hawaii Five O) type breaker. Its characteristics have changed completely. Instead of orbital water motion the water now moves forward and up onto the beach. Each succeeding wave brings more water onto the beach and only a portion of it goes back. The result is a buildup of water, a pile of water getting more unstable with each succeeding wave. It is held on the beach by the breakers. Finally a part of one breaker is a bit lower than the rest and the “wall” of water breaks through and flows out to sea. This lowers the pile in this spot and the pileup up and down beach from the spot flows into the low spot and out to sea. These currents feed the rip and so are called feeder currents. They are strongest and almost restricted to the zone shoreward of the breakers. In extreme cases they are enough to knock children down and roll them into the rip current. As long as the waves bring water to the beach about as fast as it flows out to sea, the rip continues. When the waves die down, the rip ceases. The second case results in an even more pronounced rip. It occurs when a sand bar (or nearshore reef) acts as a wall, over which waves break. The wall holds the water on the beach and it finds its way back out to sea through a gap in the bar or reef. Obviously this should be a stronger rip. Often, in California, we used the strong rips to carry divers out to sea on their paddleboards, beyond the surf, but we came back in almost anywhere else but in the rip.

There was a prevailing rip current in the middle of LaJolla Bay, in southern California. The waves approaching the Bay would be refracted by both curving sides and bend so as to concentrate water and energy in the center of the Bay. This rip was very strong and dangerous. One day a man with three kids, one about 5 and two twins about 3, I’d guess, got too close to the rip and one twin was washed out to sea while he struggled to hold on to the other twin and the 5 year old. With some help he got them ashore and went to look for the third child who had disappeared. A major search was instituted, by plane, helicopter, and small boats. In addition, another Scripps diver and myself went into the rip with SCUBA gear, intending to look for the body on the bottom. We were swept out to sea so rapidly that the bottom was a blur. At the head of the rip we searched until we ran out of air and came in well away from the rip. We then tried to convince the City to put up warning signs but they refused, saying that it was bad for tourism. Today the City would be sued for millions. The poor father walked the entire shore of LaJolla Bay for several weeks but nothing was ever found. I’ve tried to swim against a rip with swim fins and found myself going feet first out to sea. Just don’t panic; swim parallel to the beach. You can often tell a rip because the water flowing out to sea beats down the incoming waves and a surface track of white foam often indicates its position. Sometimes the sand being carried out makes the rip muddier than the water around it. Watch for these tell tale signs and pay attention to the lifeguards. They are very savvy about runouts and put up warnings for you to read. Years ago I published this warning in a local newspaper. A day or two later two young men got caught in a rip and could not get back to the beach. One of them, at the last minute remembered the column and grabbed his buddy, and with the last of his strength began swimming PARALLEL TO THE BEACH! He said to a reporter that he had remembered the advice from the paper and thus saved his buddy. A Girl Scout Troop or Council in North Miami took both articles and copied them on both sides of a sheet of paper. They printed up and distributed these sheets to every school in the area so I like to think maybe I saved a few more swimmers caught in rips.

|

|

[Home] [Cirriculum Vitae] [FAU Page] [Ray's Corner] |